Much has been written about the Martini. But there’s much more to be said about the Manhattan.

It takes a lot for a gin lover like me to make such an admission. But the evidence is clear: No other cocktail has enjoyed a richer history, wielded a greater influence, or experienced more revivals and variations than that deceptively simple crimson combo of whiskey, sweet vermouth, and bitters.

“It is the father of the Martinez, the grandpop of the Martini, and the founder of all French-Italian cocktails,” wrote Gary Regan in The Joy of Mixology. “Quite simply, when properly constructed, it is the finest cocktail on the face of the earth.”

I wouldn’t go that far, but I will say this: The Manhattan is the polymath of mixed drinks. Few other cocktails, especially those based on just three basic ingredients, possess the ability to transform themselves in so many satisfying ways based on tweaks to the ingredients or whims of the bartender.

Sitting here in the early 21st century, it’s hard to imagine how revelatory, how truly revolutionary, was the creation of the Manhattan some 140 years ago.

Page through the 1862 edition of How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon-Vivant’s Companion by Jerry Thomas, widely considered the first real cocktail guide published in the United States, and you’ll see dozens of recipes calling for sugar, water, and bitters to be combined with various liquors—but the word “vermouth” doesn’t even appear in the index. In fact, it would be another decade or two before the fortified wine, formerly used mostly for medicinal purposes, became a cocktail ingredient.

That moment came, it is often said, at the old Manhattan Club around 1880 (although some sources place it as early as 1874). There, a fellow named Dr. Iain Marshall supposedly whipped up a concoction for a birthday party thrown by Winston Churchill’s mother for the governor of New York; he then named it after the club. If all of that seems unlikely, there’s an alternate history, as mundane as its counterpart is fantastic, based on one bartender’s testimony to another, attributing the drink to a third bartender named Black, who ran a bar on Broadway.

Regardless, by 1882 the formula for the Manhattan had been published in a newspaper, and two years later the recipe appeared in The Modern Bartenders Guide, or Fancy Drinks and How to Mix Them by O.H. Byron. And the uber-cocktail proceeded to conquer the drinking world.

It’s noteworthy that in Byron’s book, so soon after its creation, the Manhattan already appeared in two variations—testimony to the drink’s versatility and its receptiveness to experimentation. Those two versions—one with Italian (sweet) vermouth, the other with French (dry) vermouth—formed the first great demarcation in the drink’s ongoing permutations over the next century-and-a-half. But others quickly materialized: bourbon instead of rye whiskey? Peychaud’s bitters instead of Angostura? Dubonnet instead of vermouth?

For decades, the most popular Manhattan variation was the Rob Roy, which features scotch as its base alcohol. But as the 2000s dawned, mixologists began toying with both the components of the Manhattan and its three-ingredient formula.

As Robert Simonson details in his excellent recent history of the Manhattan, cocktail aficionados soon had to choose from a Red Hook (rye, Punt e Mes, maraschino liqueur), the Revolver (bourbon, coffee liqueur, orange bitters), the Slope (rye, Punt e Mes, apricot liqueur, Angostura bitters), and the Cobble Hill (rye, dry vermouth, Amaro Montenegro, and fresh cucumber). Not to mention the Apple Manhattan, the Red Manhattan (made with claret red wine), and many, many others.

I haven’t tried most of these, but I’m sure going to. In the meantime, my perfect Manhattan is a Perfect Manhattan—perfect in the sense that it uses equal parts sweet and dry vermouth. I also prefer bourbon to rye and Peychaud’s to Angostura.

The result is a bit drier than the original version. Which satisfies me until my next Martini.

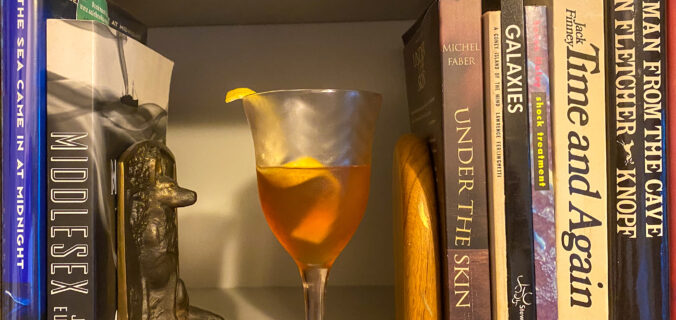

Perfect Manhattan

2 ounces bourbon

1/2 ounce dry vermouth

1/2 ounce sweet vermouth

3 dashes Peychaud’s Bitters

Lemon peel for garnish

Add liquid ingredients to a shaker or mixing glass with ice. Stir for 30 to 45 seconds. Strain into chilled coupe glass. Garnish with lemon peel.

Heartfelt thanks this week to Becca Rothschild, first Patreon supporter of the forthcoming book Sunday Specials: 52 Classic and Cutting-Edge Cocktails to Cap Off Every Weekend of the Year. If you’d like early and exclusive looks at the book’s contents, please consider becoming a Patreon backer.